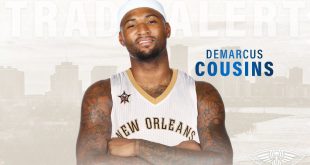

In the late hours of Sunday, February 19, 2017, the Sacramento Kings traded their best player, DeMarcus “Boogie” Cousins, to the New Orleans Pelicans for a variety of players and picks, which were, by most accounts, not equal trade value for the Kings’ All-Star center.[i] The official NBA collective bargaining agreement is barely a month old, but it has already influenced the biggest trade of the NBA season.

It’s generally a good thing that the economically booming NBA and its players didn’t panic and overreact to a wild free agency and enormous cap spike by drastically changing the terms of the CBA. But that doesn’t mean the league avoided any influence from the chaos. As a response to the recent trend of high profile free agents (e.g., Kevin Durant) leaving their teams for greener pastures, the NBA’s new CBA was designed to help teams retain their elite players.

The key tool influencing the Boogie Cousins trade was the Designated Veteran Player Extension (DVPE). Under the new CBA, teams can offer special extensions to two veteran players entering their eighth or ninth seasons. Teams can use the DVPE to extend a player for up to five years at 35% of the salary cap, a percentage usually reserved for players with more than ten years of experience. The DVPE was modeled off the Designated Player Rookie Scale Extensions available under the 2011 CBA, under which some players could earn up to 30% of the salary cap.

The extensions are limited and only apply to players who are re-signing with the team that drafted them or to players who were traded within their first four years. To qualify, the players must have been league MVP once in the preceding three years, or have won Defensive Player of the Year or been named to an All-NBA team in the immediately preceding year or twice in the previous three years. And DeMarcus Cousins just happens to qualify under those criteria.

When Kevin Durant left the Thunder to join the Warriors, Oklahoma City couldn’t pay him significantly more than Golden State for the first four years of a contract. The DVPE shifts that situation, providing more leverage to the team with the free agent superstar, allowing the team to offer more money in negotiations. That doesn’t mean Kevin Durant would have stayed in Oklahoma City if the Thunder had this tool available; he may still have preferred a better chance at a title with a team that has been to the NBA Finals the last two years. But in theory the DVPE should help teams retain stars by making staying home far more lucrative.

Cousins won’t become a free agent until the summer of 2018, but the Kings obviously had this massive extension contract on their minds because Cousins would have been eligible for the extension this summer in 2017. It would have been the largest contract in NBA history, a five-year $209 million contract extension, keeping him in Sacramento through 2023. The Kings were obviously concerned about the long-term financial ramifications of such an extension, in addition to deciding that they no longer wanted Cousins to be the face of their franchise.

Another key part of the extension provision is that Designated Veteran Players are ineligible for trades for the first year after they sign the extension. The theory was that this would help prevent players from signing an extension to get the extra money before quickly attempting to force a trade to another team. In reality, this likely worried the Kings even more, fearing that if they did pull the trigger on extending Cousins, that they would then be unable to unload his contract in a trade if he did something else to anger the team.

Now, Cousins can only sign a five-year contract with the Pelicans worth $180 million, which is probably why he didn’t want to be traded in the first place and why his agents widely publicized that he would not sign an extension with teams if traded. Money talks. Of course, Cousins isn’t the only player who will be eligible for the DVPE. For example, the rule will also apply to Stephen Curry this summer, though it is obviously unlikely that the Warriors would trade Curry for fear of being saddled with his contract, the way the Kings did with Cousins.

The other weird CBA footnote to this trade is that the Kings don’t actually control much about their 2017 first round pick. Long story short, if the pick is outside the top-10, the Bulls get it (the Kings traded the pick to Cleveland, which traded it to Chicago). So the Kings have an incentive to tank in order to keep the pick in the top-10 and have a chance to select a good player at the top of the draft, rather than lose the pick to Chicago. But they can’t tank too hard – the 76ers have the right to swap picks with the Kings, so if the Kings were to somehow wind up with a better pick than the 76ers, they would lose the pick anyway. Of course all of this maneuvering could have been avoided, if the NBA had just followed my plan and done away with tanking. But that will have to wait for another CBA.

Collective bargaining is a complex process that involves a number of detailed provisions. Often both parties think certain provisions will produce certain results, and it’s not until later that the unintended consequences of the agreement are known. The irony of the Designated Veteran Player Extension is that it was designed to help teams keep their star players. In Sacramento’s case, it goaded the Kings into a quick decision: tie the franchise financially to a player with a problematic history who has never brought the team to the playoffs, or trade him before the opportunity for the extension even arises? They chose the latter, and the Pelicans are thankful they did.

[i] The official trade terms: New Orleans received DeMarcus Cousins and Omri Casspi from Sacramento in exchange for Buddy Hield, Tyreke Evans, Langston Galloway, and the Pelicans’ 2017 first and second round draft picks.

The Sports Esquires Putting Sports on Trial

The Sports Esquires Putting Sports on Trial